Menu

Scientific Scholar Awards

Awardees

Scientific Scholar Awardees

Each year we support multiple Scientific Scholars with $60,000 each for their proposed research. Each award recipient names a mentor who will help guide him or her through the process of becoming an established researcher.

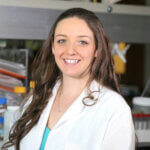

Sneha Saxena, PhD

Massachusetts General Hospital

2022 James A. Harting Scientific Scholar Award

Learn More